Named after Sir Thomas Makdougall Brisbane

From Southland of the Holy Spirit

Southland of the Holy Spirit

Sir Thomas Makdougall Brisbane was born on 23 July 1773 near Largs in Ayreshire in the lowlands of Scotland. His father, a veteran soldier, had an ancestor who had been Chancellor of the Kingdom of Scotland, while his mother was a descendant of King Robert the Bruce. Brisbane was educated at home by his God-fearing mother and several Presbyterian ministers or tutors, and at the University of Edinburgh, where he developed a love for astronomy and mathematics. In 1789, Brisbane joined the army, and the following year, while an ensign in the 38th Regiment, he met and formed a lasting friendship with Arthur Wellesley, later Duke of Wellington. In 1795 Brisbane learned the practical uses of astronomy after he escaped from a shipwreck in a voyage to the West Indies. He served in the West Indies, Spain, France and Canada. He was knighted in 1837, receiving the Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath for his part in the Peninsular War, and rose to the rank of General in 1841. In 1818 Brisbane returned to Scotland to resume his studies in astronomy, and the following year he married Anna Maria Makdougall of Makerstoun, Scotland. In 1820, Wellington (and Sir Joseph Banks) recommended to Lord Bathurst that Brisbane succeed Governor Macquarie. The story goes that Bathurst, remembering Brisbane's love of astronomy, said he wanted "one that will govern not the heavens, but the earth in New South Wales". Brisbane asked Wellington if his scientific studies had ever interfered with his military duties. "Certainly not", replied Wellington, "I shall write to his Lordship that, on the contrary, you were never in one instance absent or late, morning, noon, or night, and that in addition you kept the time of the army".

So in 1821, Brisbane accepted the appointment. One of Brisbane's greatest successes was to cut down on government expenditure. As a result of the Bigge Report, Brisbane introduced several reforms. He limited the size of land grants and specified that landowners must employ and maintain one convict for every 100 acres. This policy helped to curb land hunger. "Not a cow calves in the colony but her owner applies for an additional grant in consequence of the increase in his stock", he wrote. He organised convict administration, making it pay for itself by hiring out gangs of convicts to settlers for clearing land, and made the government farms self-sufficient. He abolished censorship of the press in 1824, introduced trial by jury, and reformed the currency.

Another of Bigge's recommendations that Brisbane put into effect was the segregation of convicts of different classes. The more educated convicts of good behaviour were sent to Bathurst or Wellington, while convicts twice convicted were sent to special penal stations. As a consequence of these changes, coastal exploration was encouraged. This resulted in the discovery of the Brisbane River. Brisbane also sponsored the journeys of Hume and Hovell to Port Phillip, and of Allan Cunningham to Pandora's Pass, and encouraged the emigration of young settlers by giving them money. These pioneered the areas around Bathurst, Maitland, Goulburn and Campbelltown, and "squatters" settled the country further west. As a result, the population of the colony increased from 33,500 to 52,500 during Brisbane's administration.

Brisbane, in taking up his post as governor, inherited all the sectarian squabbles, political intrigues, and land wars between the "exclusives" and emancipists. A devoutly religious and a peace-loving man, Brisbane was reluctant to enter into the disputes between the Anglicans and the Roman Catholics or between the "exclusives" and the emancipists. However, Brisbane was not afraid to take a stand on moral issues. In a private letter, dated June 1824, he wrote: "There is no object I have more sincerely at heart, than the advancement of morality in these colonies". He supported Bible and tract societies. He respected "the hallowed rights of conscience", despite the disapproval of certain Church of England clergymen, who had no sympathy for "heretics". Brisbane was motivated by the memory of a kindly paternal Methodist aunt and he believed the Methodists were "a highly valuable and respectable body, who [did] much good". He helped them to establish an Aboriginal mission, granted the Church Missionary Society (CMS) 10,000 acres as an Aboriginal reserve, and arranged for aid for the Roman Catholics to build St Mary's Church. Brisbane would not tolerate a party or a greedy spirit. He refused aid to the Presbyterians when their minister, Rev. John Dunmore Lang, declined to hold a service under the same roof as the Roman Catholics. He angered the Anglicans when he refused their bid to take over the government lands at Grose Farm (later the site of Sydney University), as well as the Domain, and the prison farm at Emu Plains. He told Archdeacon Thomas Scott that the church had "amply sufficient" land.

Brisbane opposed excessive corporal punishment, gave reprieves to many prisoners sentenced to death, and helped the emancipists get land grants--a policy which angered the senior chaplain, Samuel Marsden, who favoured the righteous law-abiding "exclusives" . Marsden, smarting from the Douglas judicial inquiry, trumped up charges against Brisbane and Frederick Goulburn, the Colonial Secretary of New South Wales, who was already at odds with Brisbane due to the governor's generous attempts to repair the breach with the Presbyterians. Because of Brisbane's weakness as an administrator, his subordinates often sabotaged his orders. The main offender, Goulburn, used to alter the Governor's orders, or issue his own without Brisbane's consent. As a result of the controversy, fuelled by Marsden's malicious letters to Lord Bathurst, the Colonial Office recalled both Goulburn and Brisbane. However, Brisbane's conscience was clear. He wrote:

I can exultantly state, in the face of the Colony and the world at large, that no human being can accuse me of an unjust, illegal, cruel, or even an improper act, as of all these my internal monitor fully acquits me.

On his return to England, Brisbane devoted the rest of his life to science, philosophy and agriculture. Brisbane's achievements in astronomy brought him more fame than his military career or his accomplishments as Governor of New South Wales. He established two observatories in Scotland and built another at Parramatta. In 1827, he became Vice-President of the Astronomical Society. When Sir William Herchel presented Brisbane with the gold medal of the Astronomical Society in 1828, he called him the "founder" of Australian science. Brisbane was also the first President of the Philosophical Society of Australia. He received honorary degrees from the universities of Edinburgh (1824), Oxford (1832) and Cambridge (1833), and became President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1833, serving in that capacity until his death.

Brisbane died in 1860 in the same room in which he was born. He was survived by his wife. Their four children had died earlier. Manning Clark, in his appraisal of Brisbane, wrote:

From the earliest days, Brisbane had lifted up his eyes away from the world towards the heavens in more senses than one. Those who judged by appearances, and what a man gave out about himself, took him as a Christian, a scholar, and a gentleman.

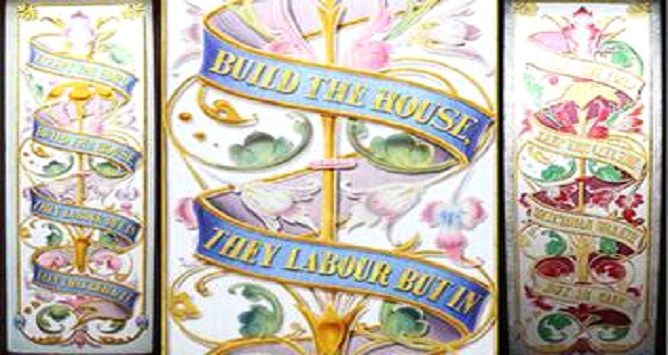

Queensland Parliament House Bible Verse

The two ground floor stained glass windows feature text from The Bible, Psalm 127-1, stating:

Except the Lord build the house, they labour but in vain that build it.

Except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain.

This text was chosen by Mrs Elizabeth Emily O’Connell (nee le Geyt), who was the wife of Sir Maurice Charles O’Connell, the second President of the Legislative Council.