By Elizabeth Rogers Kotlowski

While all exploration has its dangers and difficulties, explorer Ernest Giles wrote: "Exploration of one thousand miles in Australia is equal to ten thousand miles in any other part of the earth's surface, always excepting Arctic and Antarctic travels".[1] The immense size of the continent and the aridity of the interior were major problems. Water was a constant preoccupation of the explorers. For example, explorer Eyre travelled 1500 miles from Spencer Gulf to King George's Sound without finding running water once. The explorers sometimes found rainwater in hollows in rocks or clay; they rose before dawn to gather the dew, Aboriginal style; mostly they dug for water.

Food was the second concern. While the Aborigines had an unlimited menu of edibles--from salt and freshwater fish, to frogs, fungi, the seeds of leguminous plants, the larvae of insects, white ants, and birds' eggs, the white men did not have a palate for many such delicacies, nor had they been trained in bushcraft. The Aborigines, being nomads, went where the food was to be found; the explorers had a geographical objective in mind so they had to take food with them. Some drove flocks and herds to provide fresh meat. Explorers Charles Sturt and Thomas Mitchell loaded food supplies, such as bacon, flour, sugar and tea onto carts; however, while travel with carts or herds of sheep or cattle ensured a food supply, it was very slow and put heavy demands on water consumption. Eyre and others preferred to travel light, using packhorses or camels, so they could move faster. They ate sparingly, and if not able to obtain fresh meat by hunting, as supplies dwindled, they killed their pack animals. The diet of the explorers included smoked horse meat, dried beef and dry bread. Boiled camel-heel was a treat. Fresh fruit and vegetables were a rarity so that most of the explorers suffered from malnutrition, especially scurvy, and eye troubles caused mainly by desert glare and blowing sand.[2] Another trial was the torment from ants by night and flies by day. Explorer George Grey wrote:

Another hazard the explorers faced was the constant danger from hostile Aborigines, who rightly saw the white men as making them "strangers in their own land".[4]The maintenance of night watches was a drain on the strength of the explorers, but if they neglected to do so, there were often fatal results. On the other hand, because of the Aborigines' knowledge of bushcraft, explorers often included them in their parties and often owed much to their practical kindness.

An understanding of the difficulties the explorers faced will give the reader an appreciation of the heroic deeds and sufferings of these brave people. What motivated the explorers to endure such incredible hardships? What kind of men were attracted to come to Australia? Thomas Mitchell, Charles Sturt, George Grey, John McDouall Stuart and Peter Warburton were military men who normally would have found an outlet in martial deeds back in Britain. But they were men looking for adventure--men intrigued by the romanticism of the southern continent. Or, they were men who were enamoured by the uniqueness of its plant and animal life, like Ludwig Leichhardt who had an interest in natural science. They were all men who loved freedom. Whether inspired by a fervour for "God, gold, or glory", nature, or public service, they were men with a passion, a dream. Sturt dreamed of an inland sea. Native-born John Forrest was a government surveyor. Ernest Giles confessed exploration itself was a passion, like that felt by one human being for another. In his book, The Romance of Exploration, he wrote: "The romance is in the chivalry of the achievement of the difficult and dangerous, if not almost impossible tasks. An explorer is an explorer from love, and it is nature, not art that makes him so".[5] This desire in man to overcome obstacles is an inherent part of the nature of man, implanted by God when He made Adam. The seed of this nature was already in man when God said to Adam: "Be fruitful and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moves upon the earth" (Gen. 1:28).

Early land exploration was slow because of the nature of the settlement, which was literally a gaol. On the one side was the Pacific Ocean and on the other the impenetrable barrier of the Blue Mountains that formed part of the Great Dividing Range running from Cape York in the north to Wilson's Promontory in the south. Even Governor Phillip realised that the colonists could make no progress until they crossed the Blue Mountains. He and others tried and failed. It was not until 1813 that explorers Gregory Blaxland, William Lawson and William Charles Wentworth traversed this difficult terrain and discovered the great pastoral lands to the west. But Charles Sturt's unrivalled feat in unravelling the mysteries of Australia's only great river system in his 1829 expedition was the most important achievement in the history of Australian exploration. [6]

Once the Blue Mountains had been crossed, the obvious direction of exploration was westwards, but others went north and south. The discussion of land explorers in this chapter is restricted to those who together walked the depth and breadth of the significant land.[7] Sturt went south and west as far as South Australia. Eyre continued this westward move (he was the first to cross the continent from east to west); Grey travelled up the west coast. Forrest crossed the interior from west to east as far as the Overland Telegraph, which John McDouall Stuart made possible when he crossed the continent from south to north. Warburton crossed the continent from Adelaide in the south to the north-west coast; Leichhardt opened up the north-east. A description of pioneer John Flynn's protection over the Inland, and his vision for "Christ and the Continent" will be given in the next chapter. But before discussing the land explorers, the author will turn to a sea explorer, Lieutenant Matthew Flinders, the man who gave shape to Australia.[8]

Matthew Flinders was born at Donington in Lincolnshire on 16 March 1774, the son of Matthew Flinders, a surgeon, and his wife Susannah nee Ward navy. He was educated at Cowley, the local Free School and Horbling Grammar School, where he studied English, Latin and Greek to prepare a career in medicine. Flinders' father was keen on his son's becoming a doctor like himself, his grandfather and his great grandfather before him. But while at school, Flinders read Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe[9], which changed his life. Young Flinders decided to go to sea, instead of pursuing surgery. He had a natural aptitude for mathematics, and for a year he remained at home, assiduously studying mathematics, astronomy and navigation. His Uncle John Robertson's Elements of Navigation, which taught how to steer by the stars; and Moore's Principles of Trigonometry, which showed him how to measure distances, heights of mountain, and widths of rivers. A weekend visit to the home of Admiral Pasley, arranged by his cousin Henrietta, who was governess to Pasley's daugthers, led Pasley to invite Flinders to join the navy. [10] So in 1789, at the age of fifteen, Flinders enlisted in the Royal Navy.[11]

In 1791 he served as Midshipman under William Bligh on his voyage to Tahiti. On his return to England, he served in HMS Bellerophon at the naval battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794. The following year, he sailed for Port Jackson on the HMS Reliance, on which George Bass was surgeon. After arriving in New South Wales, Bass and Flinders began a famous series of explorations. In a small eight-by-five-foot open mackerel boat that they had named Tom Thumb, and had brought out from England on the Reliance, they explored Botany Bay. In 1796, they built a larger boat that enabled them to explore the southern coastline. On one occasion, they encountered aggressive natives at Five Islands. While Bass was busy drying out their boat, supplies and gun powder, Flinders kept the Aborigines entertained with a pair of scissors which he used to trim the beards and hair of the men.

In 1798 Bass and Flinders set out in the sloop Norfolk (of only 25 tons) to circumnavigate and chart Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), proving it to be an island. Flinders named the sea between Tasmania and the mainland of Australia Bass Strait, after Bass who first discovered it in 1797.[12] In 1800, Flinders returned to England and proposed that Britain sponsor a voyage to circumnavigate the entire continent of Australia. His suggestion was warmly supported by Sir Joseph Banks.

In 1801, the Admiralty put Flinders in command of the Investigator and commissioned him to explore the southern "Unknown Coast", stretching from the head of the Great Australian Bight to the Victorian border. In April of the same year, Flinders married Ann Chappell of Lincolnshire, and requested permission to take her with him, but the Admiralty refused. From the time of Flinders' wedding in July, it was nine long years before he saw her again.[13]

In 1802-03, Flinders circled Australia, meticulously charting its coastline. Flinder's objective was "to make so accurate an investigation of the shores of Terra Australis that ... with the blessing of God, nothing of importance would be left for future discoverers upon any part of these extensive coasts".[14] All through 1802, he made a painstaking survey of the southern coastline of Australia, discovering the state of South Australia, and he was the first explorer to visit the site of the future state capital, Adelaide. His navigation of Spencer Gulf exploded the theory that the southern continent was divided into halves (New South Wales in the east and New Holland in the west) by a channel running from the Gulf of Carpentaria to the Great Australian Bight in the south. Flinders continued his exploration of the southern coastline to Port Phillip, present site of the Victorian state capital, Melbourne. When he arrived in Sydney on Port Jackson, Flinders refitted his ship and continued his exploration of the coastline northwards, making a detailed survey of the Queensland coast and the western and southern shores of the Gulf of Carpentaria.

However, his ship needed repairs so he returned to Port Jackson via the west coast. Flinders set out again for England in August 1803, but a week later his ship, the Porpoise, was wrecked on a coral reef. Leaving Port Jackson again in the Cumberland (of 29 tons), Flinders sailed north again into the Indian Ocean, but was forced to stop at the small French island of Mauritius (500 miles east of Madagascar) for repairs. While he was there, Flinders--unaware of the war between England and France--was mistaken for a spy by the French and was put under arrest for six-and-a-half years. During this time Flinders worked constantly on his precious charts and journals, but his health deteriorated from scurvy and kidney disease. Following the British blockade in 1810, he was released and returned to England to be reunited with his "bride". Two years later his wife, who had been faithful to Flinders for nine years, bore him a daughter, Anne, who later became the mother of another famous explorer, William Matthew Flinders Petrie, the noted Egyptologist.

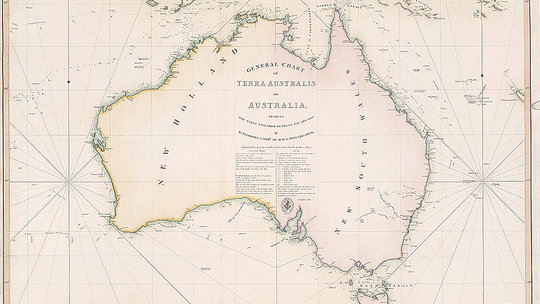

Flinders was promoted to Post Captain, but the Admiralty would not backdate his pay; therefore, he spent the remaining four years of his life in poverty, living on half-pay in failing health. During this time, he worked on his book, A Voyage to Australia, although Sir Joseph Banks crossed out "Australia" and inserted the Latin name, Terra Australis . Flinders was the first man to use the name "Australia". The proofs of the two volumes, with his atlas and charts, were placed in his hands as he lay dying. He died the same day on 19 July 1814, just 40 years old.

Matthew Flinders was among the world's most accomplished navigators and hydrographers, though most of his explorations were done in small, unsuitable, rotten boats. In his short lifetime, Flinders circumnavigated Australia, including the island of Tasmania; made the first navigation maps of thousands of miles of coastline; and contributed to the science of navigation (including his invention of the Flinders Bar). At the age of 24, he was the youngest captain in the Royal Navy, except for Nelson, who became captain at age 21. Unlike Nelson, Flinders died unknown and penniless. But the deeds that men do live after them. He was a man of integrity--of diligence, determination, courage, and sacrifice in duty, and tender love and faithfulness in marriage. He is remembered in the many memorials to his name in Australia--Flinders Ranges, Flinders Bay, Flinders River, Flinders Passage, Flinders Street, Flinders Railway Station. Many islands, headlands, lighthouses (and even Flindersia tufted yellow fodder grass) have also been named after him. Australians will remember Flinders as the man who put Australia on the map. As a result of his discoveries, much new land was opened up.[15] His maps of the coastline were later used by inland explorers Eyre and Leichhardt. However, before the inland could be explored, the Blue Mountains had to be crossed.

Map of Australia by Matthew Flinders of 1814 (National Library of Australia ref: nla.map-t570)

Bending like a bow behind the settlement and rising like a medieval fortress from the coastal plains, the Blue Mountains (though no higher than five thousand feet) were no ordinary regular mountain ranges, but a confusion of jagged rocky ridges and deep treacherous gorges that erupted in a formidable disarray--resisting all the assaults of the white man.

Leaving on 11 May 1813, Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson, their four servants, five dogs and four packhorses, left Blaxland's farm at the South Creek in the Hawkesbury River area. That night they camped at the foot of the first ridge and started climbing the next morning. As they ascended the mountain, on either side of them the gullies became deeper and the slopes more rocky. They began to mark their track by cutting the bark of the trees on both sides so they could find their way back to the camp, where they had left the horses with two of the men. The party had to literally cut their way through the scrubby brushwood, which was very thick in places. After clearing a five mile trail, they retraced their steps to the camp. The next day, they followed the same tedious routine, but they were only able to clear an additional two miles because of having to retrace their steps seven miles. They found no grass for the horses the whole way.

On Sunday they rested and made their plans for the next day. The dogs killed two small kangaroos for dinner, but some of the men started ruminating on the dangers of the expedition, and would only agree to continue after much persuasion. Sunday night, the dogs were coming and going and barking a lot, and at daybreak the men were awakened by a tremendous howling of dingoes, who had been watching them all night. After packing as much grass as they could onto the horses, along with all their other gear, the party continued on, following the path they had made during the two days before. Monday night they camped on a narrow ridge between two deep gullies. To get water, the men had to lower a bucket six hundred feet down the side of the precipice. There was not enough for the horses. The next day, the party followed the same routine of cutting a trail and retracing their steps to the camp. The ridge, which was only fifteen to twenty yards wide between two precipices, became almost impassable at one spot when they ran into a perpendicular rock thirty feet high that completely blocked their path. The men were able to make a narrow track through the centre of the rock by removing some stones wedged in the centre of the larger rock. The party continued on. Sometimes they saw an emu or a wallaby; they also found the remains of native huts or fires, and stone shavings (which they used to sharpen their spears). On Friday night, the dogs ran off and barked violently, and they heard someone run through the brushwood. They found out later that they had been in great danger. An Aborigine had tracked them down and was poised ready to spear them by the light of their fire, but the dogs had driven him off.

The western slopes were much colder than the eastern. The grass was withered and brown and when they woke up, the ground was covered with thick frost. The leg of a kangaroo that the dogs had killed was frozen stiff (though the men enjoyed the fresh meat after living on salted meat). Coming down the mountain was a treacherous affair. The sides were so steep that the men had to cut small trenches with a hoe, so the horses would not slip. They were barely able to keep their footing without the baggage, so the men had to carry the gear. Upon reaching the bottom, the horses were rewarded with good grass and plenty of fresh water. It had taken the party twenty days to cross the Blue Mountains. Though it was only a distance of fifty miles, the men had actually covered the territory three times. Finding a hill in the shape of a sugar loaf, they climbed to the summit to get a better view of the country. Before them, stretching as far as their eyes could see, were the great western plains. Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson were very satisfied to find enough forests and pasture "to support the stock of the colony for the next thirty years", and returned to Sydney with the good news.[16] At last, the prison gates were opened, and in a few years, men, with their horses, sheep and cattle, goods and chattels, were pushing eagerly through the Blue Mountains to the sumptuous grasslands beyond, because three men persevered and went further than the rest.

Captain Charles Sturt, Australia's most well-known inland explorer, was one of those who followed Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson. Sturt opened up most of southern Australia to free settlers. Born in Bengal, India, on 28 April 1795, Sturt was the son of Thomas Napier Lennox Sturt, an English judge with the East India Company. The young Sturt was sent to England at the age of four, and after attending a private preparatory school was admitted to Harrow, at the age of 15. In 1813 he joined the army and served in Spain, Canada, France and Ireland before his regiment was ordered to Sydney in 1826.[17]

Governor Ralph Darling had a high opinion of Sturt and appointed him his Military Secretary. Sturt became friendly with explorers John Oxley, Allan Cunningham and Hamilton Hume. In 1828, Governor Darling asked Sturt to lead an expedition into the interior to map the course of the Macquarie River and explore the country to the west. In carrying out his commission, Sturt discovered a large river which he called the Darling.

Sturt was a man of courage, faith and prayer. He kept a journal in which he wrote of his faith and of how he constantly took all his plans, difficulties and sorrows to the Lord in prayer. "Sturt, like most Australian explorers faced with a hostile environment, leaned hourly on God's mercy". At night he slept with a Bible that had belonged to his father-in-law under his pillow. When he had to throw away most of his possessions in the desert, he kept his Bible in preference to an oil lamp.[18] Through prayer and the reading of his Bible, Sturt found wisdom and strength to endure, and peace, even in times of danger.

Something more powerful than human foresight or human prudence, appeared to avert the calamities and dangers with which I and my companions were so frequently threatened; and had it not been for the guidance and protection we received from the Providence of that good and all-wise Being to whose care we committed ourselves, we should, ere this, have ceased to rank among the number of His earthly creatures.[19]

Sturt's party followed the Murrumbidgee until their way was blocked by a swamp. Leaving their horses and drays behind, they proceeded in a whaleboat until they came to "a broad and noble river",[20] which Sturt named the Murray.

They continued down the Murray River to the junction of the Murray and the Darling rivers, where their boat was shoaled on a sandbank. A group of 600 Aborigines, painted and armed, made menacing gestures accompanied by a war-song. Sturt made signs to the natives to desist their threats, but without success. As Sturt's party drew closer, the natives raised their spears, ready to hurl them. They were painted in various ways. Some, having painted their ribs, thighs and faces with a white paint, looked like skeletons. Others had painted themselves with red and yellow ochre and smeared themselves with grease, so that their bodies shone. In the background, the women, who carried supplies of darts, looked as if they had a bucket of whitewash thrown over them.

Seeing that it was going to be impossible to avoid an engagement, Sturt reluctantly picked up his double-barrelled shot gun, hoping that if he shot one of the natives, it would be sufficient to scare off the rest without further loss of life. At the very moment when he had his gun levelled at the closest native, with his hand on the trigger, he was checked by one of his men who drew Sturt's attention to a new party of natives that had arrived on the other bank. One of the Aborigines, whom Sturt recognised as being friendly from further up the river, leapt towards the native on whom Sturt had his gun trained, and seizing him by the throat, pushed him backwards, along with the other natives who were threatening to attack the party. Sturt noted in his journal how their lives were saved because of the "miraculous intervention of Providence in our favour".[21]

They were able to resume their journey down the Murray and shortly afterwards discovered the junction of the Murray and Darling on 23 January. From then on the going got tougher as they passed through an "inhospitable country" and the men became weak from lack of food. On 9 February 1830, they arrived at a beautiful lake, which Sturt called Alexandrina Reservoir, where the Murray flowed into the sea. So the mystery of the rivers was solved.

Sturt's party, "very weak from poverty of diet and from great bodily fatigue", had the arduous task of rowing 900 miles upstream back to where they had left the horses and drays. The story of the party's return up the Murray is one of the most heroic episodes in Australian history. In order to make the rations last until they reached the depot, Sturt estimated that they would have to make the return trip--against a strong current--in the same time they took to row downstream. So they decided to row from dawn to 7:00 or 9:00 p.m. each day, stopping only for one hour's break at midday. That calculation was based on circumstances being favourable. No allowances were made for delays due to bad weather, illness or trouble from the Aborigines. To perform such a feat, it was unthinkable to reduce the men's rations to less than three quarters of a pound of flour per man per day.

The party left on 13 February. It took them only 23 days, rowing upstream (as compared to 26 days down) to reach the Murrumbidgee. Six days later, on 23 March, they reached the depot. It was an incredible feat. However, the depot was deserted, so the exhausted half-starved men had to row for another 19 days against the flooded Murrumbidgee. Sturt's men were uncomplaining, but some fell asleep at the oars. One became delirious and all suffered from malnutrition or scurvy and exhaustion.

In spite of the oppressive heat, threats from natives, and the low spirits of his men, Sturt remained calm and confident that God would bring them through. On reaching their camp opposite Hamilton's Plains, ninety miles from a depot at Pontebadgery, Sturt decided to stop, since their supplies were almost exhausted. He sent two men ahead to the depot to get provisions. After waiting eight days for their return, they were just preparing to break camp, since they were down to their last ounce of flour, when the two men returned with supplies. They continued the homeward journey on foot, reaching Sydney on 25 May, six months from the time they had started out. Sturt fell on his knees, and with tears of joy thanked God for His help.[22]

Sturt's second journey was one of the most important explorations in Australian history because it explained the continent's river system and opened up much good pastoral land, thereby making way for the settlement of South Australia. However, the journey had taken a toll on Sturt's health; subequently, he went almost totally blind, and never completely regained his vision. A few years later, in 1838, Sturt completed the charting of the Murray from the point where Hume and Hovell crossed it in 1824 to the Murrumbidgee junction, which Sturt himself had discovered in 1829.

In 1844-45 Sturt made a third exploratory journey. This was his famous Central Australian expedition, the most difficult and dangerous of them all. In 1842, Sturt commented: "Let any man lay the map of Australia before him, and regard the blank upon its surface, and then let him ask him if it would not be an honourable achievement to be the first to place a foot in its centre".[23] That was Charles Sturt's ambition. Now that the riddle of the rivers had been solved, Sturt set out again to solve the riddle of the inland. On 10 August 1844, Sturt's party left Adelaide with 15 men, 6 drays, a boat and 200 sheep. Before their departure that morning, Sturt spoke at a breakfast given in his honour:

Wherever I may go, to whatever part of the world my destinies may lead me, I shall yet hope one day to return to my adopted home, and make it my resting-place between this world and the next. When I went into the interior, I left the province with storm-clouds overhanging it, and sunk in adversity. When I returned, the sun of prosperity was shining on it, and every heart was glad. Providence had rewarded a people who had borne their reverses with singular firmness and magnanimity. Their harvest fields were bowed down by the weight of grain; their pastoral pursuits were prosperous; the hills were yielding forth their mineral wealth, and peace and prosperity prevailed over the land. May the inhabitants of South Australia continue to deserve and to receive the protection of that Almighty power, on whose will the existence of nations as well as that of individuals depends![24]

Leaving Adelaide was difficult for Sturt because he was leaving behind his wife Charlotte with four children under nine years of age. His love for his wife and family were evident in the detailed letters he wrote to her while on the expedition.[25] On reaching Moorundie, Sturt regrouped and gave final instructions to his men. Lastly, he reminded them that:

Since they were about to commence a journey from which no one knew who would be permitted to return, I thought it was a duty they owed to themselves, to ask the guidance of that Power which could alone conduct them in safety through it, and having read to them a short prayer which I had prepared for the occasion to which I added the Lord's Prayer, I intimated to Mr. Poole that he was at liberty to proceed on his way.[26]

In order to avoid Eyre's "impenetrable Lake Torrens ", Sturt decided to skirt around it by following the Murray River to its junction with the Darling, then follow the Darling to its great bend at Menindee, and strike north-west from there. On 12 January 1845 the party arrived at Milparinka, where there appeared to be a permanent creek. Sturt decided it would be a good resting place before his next advance. In fact, it became their prison for the next six months. There was no water to the north and the drought had dried up all the pools to the south. The heat was unbea rable, 132 degrees in the shade and 157 degrees in the sun! Robert Flood, the overseer of the stock, complained that the top of his head was burning, while the horses drooped theirs as if overcome with drowsiness; the ground was so hot that the horses pawed at it, trying to find a cool spot. At the end of February, Sturt noted:

Every article we have went to ruin before [the heat]; the teeth of our combs fell off, the handles of our razors split, every box warped, and every nail was loosened. Our tires fell off the wheels, and the drays rattled all over. The soles of the men's shoes were fairly burnt off.... The dogs would not stir from the water but remained on the bank, after having gone into it up to their necks, repeating their bathing as soon as they were dry.[27]

The men, including Sturt himself, also suffered from the effects of scurvy. Sturt's gums were swollen, his nose bled constantly, and he had violent headaches. As the disease progressed, Sturt's assistant, Poole, lost the use of his legs, the skin of his legs turned black, and large pieces of flesh hung down from the roof of his mouth.[28] The heat was intolerable and the drought continued without a single drop of rain.

Day after day and week after week the sun rose and set in [untiring] splendour, and every cloud that rose on the horizon was beat back by a moon as bright and I almost said as hot as the sun itself. [After six months] we had nothing new to engage the attention or to attract the eye. Nothing could exceed the desolation around us. Not a herb or flower was to be seen but the land was perfectly bare and scorched. The water we were drinking became putrid and diseased itself.[30]

Sturt wrote to his wife, Charlotte: "I trust ... God will yet permit my return, and that this severe trial will issue in our final good. Such at all events is my prayer, my daily prayer to the fountain of All Mercy".[31]

By May the waterhole had shrunk from nine to two feet in depth. On 12 July the drought broke. Sturt noted in his journal: "Had the drought continued for a month longer than it pleased the Almighty to terminate it",[32] they would not have survived. To conserve provisions, Sturt decided to send most of the party, under the charge of Poole, back to Adelaide. However Poole, still very ill, died on 16 July.

Sturt, with four men and provisions for 15 weeks, pushed north-west in the hope of finding a mountain range near the centre of the continent. He was determined "to trust to the goodness of Providence to release me to push on when He thought best".[33]He crossed Strzelecki Creek, Cooper Creek, the Diamantina River and Stony Desert (later to bear his name). On 8 September 1845, Sturt reached his farthest point (latitude 24 degrees 40 minutes S., longitude 138 degrees E.) in what is now the Simpson Desert. He was 70 miles from the tropics, but was forced to retreat. Always sensitive to the needs of his men, Sturt had noticed that his partner Browne was "suffering very acutely". Sturt's journal later revealed his compassion: "A sudden thought struck me on which I determined immediately to act. I gave up the attempt to push on and told Mr. Browne that I had resolved on returning to the depot".[34] So they retraced their steps to Fort Grey, 443 miles away. Sturt described how he made that return trip in a letter to his wife, dated 21 September 1845:

I could not have hoped for water for 140 miles after leaving the creek and, believe me, it would have been a difficult job to have got our poor exhausted animals over such a distance without water, but I as I also told you, it pleased God, in this moment of our difficulty, to send rain that was sufficient for our relief and no more.[35]

Sturt's little party went from waterhole to waterhole, from puddle to puddle, arriving back at the depot on 2 October, but Sturt was off again a week later, leaving Browne in charge of the main party at the depot. When Sturt requested that Browne, the Medical Officer, remain behind, he told Sturt "he could not and would not desert [him] in such an infernal desert as this, that [Sturt] had always treated him like a brother and that he'd sooner die than return to Adelaide without [him]".[36] Sturt reluctantly parted with Browne and headed north to Cooper's Creek, which he explored eastwards for some distance, and once more he trudged through the Stony Desert. However, Sturt began to show the strain from the long sustained hardships--the shortage of water, fresh food, and the severity of the heat which was like a "fiery furnace". After his thermometer, graduated to 127 degrees Fahrenheit, burst, Sturt decided to return to the depot. Very disappointed, he wrote: "Providence had denied that success to me with which it had been pleased to crown my former efforts". He felt he was "a blighted and blasted man over whose head the darkest destiny had settled".[37]

The depot, however, was deserted. Buried in the sand, Sturt found a bottle containing a letter from Browne. Because of lack of water, the men had been forced to return to the old Rocky Glen Station, as no rain had fallen since July. When Sturt reached there on 17 November, he collapsed with scurvy. Sturt was carried on a dray another 270 miles to the Darling. They found sufficient water along the way to stay alive, and with the aid of some Aboriginal food, Sturt began to feel better by the time they arrived in Adelaide on 19 January 1846.

Sturt had travelled over 3000 miles into unknown territory. Although he was disappointed with the results, having found neither an inland sea nor a significant mountain range at the 28th parallel, the expedition had been a feat of great courage and endurance. In May 1846 Sturt received the gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society for his work.

However, the Central Australian expedition had seriously affected his health, especially his eyesight, so that he was not able to accept an appointment as Colonial Secretary. In 1853, Sturt left South Australia to return to England with his family for the sake of his children's education, and he spent his last years in Cheltenham, being widely respected and consulted on Australian affairs. Formalities were in progress for Sturt to receive a knighthood, when in June 1869 he died suddenly. However, the Queen permitted his wife to use the title "Lady Sturt".[38]

In his journals, Sturt has documented his great discoveries, as well as numerous scientific observations, and his Christian faith. He constantly recognised the Providential care[39] and intervention of God, and he was a model of Christian character. He was known for his ability to inspire and maintain the loyalty of his men (even under the most adverse conditions),[40] for his constant care for their welfare,[41] and for his conciliatory treatment of the natives.[42] Baron Van Muelle, writing in 1865, described him as "the greatest Australian explorer" and commented: "One of his qualifications was he was a gentleman, always kind and considerate of those working with him. He inspired others such as Leichhardt and Eyre by his great example".[43]

Edward John Eyre was born on 5 August 1815 in Hornsea, Yorkshire. He was the son of Rev. Anthony Eyre, an Anglican clergyman, and Sarah, nee Mapleton. He was educated at Louth and Sedbergh grammar schools. He had prepared himself for a career in the army, but at his father's suggestion, decided to migrate to Australia instead.

Eyre reached Sydney in 1833, and after gaining some experience grazing stock, he started a series of droving trips. He overlanded cattle and sheep, first to Port Phillip and then to Adelaide. He made his home in Adelaide, which became his base for a series of explorations in search of grazing country and a route to Western Australia. In 1839 he made two trips. On his first, he reached Mount Arden in the Flinders Ranges, north of Spencer Gulf. On his second trip, he travelled from Port Lincoln to Streaky Bay and then returned to the head of Spencer Gulf . In 1840 he accompanied a shipload of sheep and cattle to Albany in Western Australia and drove them overland to Perth. On returning to Adelaide, he organised an expedition to further exploration of the interior to the north.

He set out with a party consisting of five white men, three Aborigines, 13 horses and 40 sheep. Eyre reached and named Mount Deception and Mount Hopeless, but he decided the impenetrable Lake Torrens prevented further exploration of the north so he sent his party west to Streaky Bay. Fortified with fresh supplies from Adelaide, the party pushed westwards. This turned out to be Eyre's major exploration. At Fowler's Bay, Eyre decided to cut down on the size of the party because of a shortage of water and provisions, so he sent the main party back to Adelaide , keeping only Baxter (his foreman), three Aborigines, and 11 packhorses to carry the water and provisions. Hoping to open up a stock-route to Western Australia, Eyre's objective was to reach King George's Sound, a distance of 1500 miles from Adelaide. He left Fowler's Bay on 25 February 1841.

For two months he followed the coastline of the Great Australian Bight , where several times the party almost died from lack of water. In his journals Eyre frequently acknowledged the help of the Almighty God in supplying their needs and in preserving their lives.[44] Water was always a precious commodity, frequently in short supply. On 28 March Eyre wrote: "In His mercy and protection alone our safety could now ever be hoped for".[45] On 29 March Eyre noted that their last drop of water had been drunk, but during the night a heavy dew fell. So, getting up before the sun, Eyre took a sponge, and used it to collect some of the dew on the grass and shrubs. He squeezed it into a quart pot, which he filled in an hour. The native boys did better by using handfuls of fine grass instead of a sponge, and by using a large oblong tray of bark held under the branches of trees they were able to collect a larger quantity of dew and drain it into a pot faster.

Two days later, after travelling 160 miles since the last waterhole, the men found fresh water six feet below the sand. Words were "inadequate to express the joy and thankfulness of my little party", Eyre noted. A few hours before it had seemed all hope was gone. Several horses had already died, and the men were so weak and exhausted from fatigue that it had been almost impossible to put one foot in front of the other. Eyre commented:

In this last extremity we had been relieved. That gracious God, without whose assistance all hope of safety had been in vain, had heard our earnest prayers for His aid, and I trust that in our deliverance we recognized and acknowledged with sincerity and thankfulness His guiding and protecting hand. It is in circumstances only such as we had been lately placed in that the utter hopelessness of all human efforts is truly felt, and it is when relieved from such a situation that the hand of a directing and beneficent Being appears most plainly discernible, fulfilling those gracious promises which He had made, to hear them that call upon Him in the day of trouble (Isa. 41:17-18; 43:19).[46]

As soon as each man had quenched his thirst, Eyre boiled some water for tea, and used some more to bake bread, while Baxter and the natives worked on making the well larger so they could water the horses. Eyre, in an entry dated 7 April, noted they were half-way between Fowler's Bay and King George's Sound, and had at least 150 miles of barren sand-drifts to cover without a drop of water in sight. Eyre knew they could not make it without the horses to carry the provisions and equipment, but they barely had enough water to last another week. To Eyre, the thought of going back to Fowler's Bay was unthinkable. So the next day, after filling up their kegs with water and loading their horses, the party pressed on towards King George's Sound. "We had nothing to rely upon but our own exertions and perseverance, humbly trusting that the great and merciful God who had hitherto guarded and guided us in safety would not desert us now".[47]

However, on the night of 29 April, there was a tragic event that nearly terminated the expedition. Eyre described it in detail in his journal. He hobbled the horses and turned them out to graze, while the others tore off branches of trees to make windbreaks, each twelve feet apart. The arms and provisions had been piled under an oilskin between Eyre's windbreak and that of his overseer, Baxter. Since the party had already eaten earlier in the day, and they did not have enough rations for an evening meal, it was time to settle down for the night. All that remained to be done was to arrange for the watching of the horses. The first watch was from six to eleven p.m. and the second from eleven to four a.m., at which time the party broke camp and headed out with the first streak of daylight.

This night Baxter asked Eyre which watch he wanted to take. Eyre said he would take the first watch since he was not sleepy, though tired. Baxter went to his windbreak to sleep, while Eyre watched the horses. A hard cold south-westerly wind was blowing and rain clouds partially covered the moon. As the horses fed on the scanty grass, they rambled in and out of the scrub with Eyre following them. At ten thirty, he headed them back towards the campsite, but was slow in finding his way in the darkness. He peered through the scrub in search of some clue as to the whereabouts of the campsite, but the fires had already gone out. At that moment, he saw a flash, followed by a gunshot a quarter of a mile away. He called out but there was no reply. Alarmed, Eyre left the horses and hurried towards the direction of the flash. He was met by the King George's Sound native, Wylie, who was very distraught, but all he could say was, "Oh Massa, oh Massa, come here". He followed him to the camp, where he found Baxter lying on the ground and writhing in a pool of his own blood. He died shortly afterwards. The two native boys had disappeared taking with them the majority of the expedition's meagre provisions and ammunition. His faithful friend and overseer of many years was dead. Most likely, Baxter had been awakened by the native boys when they were making off with the provisions, and in trying to prevent them, he had been shot through the heart. While Eyre went to get the horses, Wylie made a fire, so they would have some light in which to assess the situation. They found that all twenty pounds of bread were gone, along with some mutton, tea and sugar, the overseer's tobacco and pipes, a one gallon keg of water, some clothes, the two double-barrelled guns, some ammunition, and other small articles. Scattered around the campsite were the horses' harness and the remains of the stores--forty pounds of flour, a little tea and sugar, and four gallons of water, besides some useless arms and ammunition that Eyre had secured by his windbreak.

As the startling reality of the situation dawned upon Eyre, he realised the frightful truth that he was alone in the desert with one Aborigine, who even at that moment might be plotting to kill him. Another 600 miles of unknown country had to be crossed before he could expect any assistance. His only rifle was useless, while he had no way of knowing how far it was to the next fresh water hole. In such dire circumstances, Eyre was still able to see the hand of Providence in arranging such small details as Eyre's choice in taking the first shift. "Trifling as the arrangements of the watches might seem, and unimportant as I thought it at the time, whether I undertook the first or second, yet it was my choice, in this respect, the means under God's providence of my life being saved".[48]

After the dreadful horrors of that terrible night, Eyre, clothed only in a shirt and thin trousers, suffered painfully from the cold wind; his warm clothes had been among the stolen goods. Eyre and Wylie remained to perform the last rites for their unfortunate friend. However, they had camped on a surface of sheet rock that extended for miles in every direction and could not find sufficient soil to bury him. So, they wrapped the body in a blanket and left it where it fell.

The small party moved on westwards. As the sun broke seven days later, the horses were still crawling on slowly. The two men were getting very weak and worn out, as well as lame. It was only with great difficulty that Eyre managed to get Wylie to move once he sat down, and nothing but a strong sense of duty prevented Eyre from lying down and sleeping forever. As they followed the coast along the top of the cliffs, the road got worse and worse until it became a series of sandy, scrubby and rocky, ridges, and hollows. The party stumbled on until they saw some sand dunes in the distance, and two miles further on they came across a native road leading down the sides of the cliffs to the beach below. With great effort they got the horses to the beach, where they found a place where the natives had dug for water. They were again encamped at fresh water, after having crossed 150 miles of rocky, barren and scrubby tableland in seven days from the last waterhole.

The terrain improved as they left the cliffs of the Great Bight behind. However, the constant walking, the unwholesome diet, the effects of scurvy, and the effort of having to dig for water, carry firewood, harness and unharness horses, and perform other chores, left them completely exhausted. In addition, the country was so scrubby and sandy they often had to walk along the loose coarse sands of the beach, which made travelling double work. At night, though they needed rest, they couldn't sleep because of the intense cold. The act of moving at all was a great effort and Eyre's mind became languid and forgetful. Wylie was as bad, but his good temper usually disposed him to cooperate. On 18 May they saw a large kangaroo, which was a pleasant diversion. Eyre gave Wylie the rifle that he had repaired and sent him off to hunt down a kangaroo. Wylie brought a young one back at dark. It was large enough for two meals. What a feast they had that night! Eyre observed:

For once Wylie admitted that his belly was full. He commenced by eating a pound and a half of horse-flesh, and a little bread; he then ate the entrails, paunch, liver, lights, tail, and two hind legs of the young kangaroo; next followed a penguin, that he found dead upon the beach. Upon this he forced down the whole of the hide of the kangaroo after singeing the hair off, and wound up this meal by swallowing the tough skin of the penguin; he then made a little fire, and laid down to sleep, and dreamt of the pleasures of eating, nor do I think he was ever happier in his life than at that moment.[49]

Finding an abundance of good pasture, water, and edible game, the party rested for a week, to give the horses and the two men a chance to recover. The Aborigine had apparently made good use of the time. On 26 May Eyre noted that Wylie had been eating the whole night. But it was soon time to move on. Eyre continued to make careful notes on the changes in the terrain, and accompanying flora and fauna. On 31 May they found some dead grass-trees. Wylie found they were full of the white grubs which the natives are so fond of. So while Wylie enjoyed a large luxurious supper of white grubs, Eyre, who couldn't bring himself to try them, preferred the root of the broad flag-reed, which when roasted in hot ashes had a tasty mealy texture.

But they had to keep moving. Though they now had plenty of water, they were down to the last of their flour. They made their way to Thistle Cove, where Eyre intended to kill and eat the little foal for food. As they neared the sea, they saw a whaleboat sailing into the bay. Hardly able to believe their eyes, they hastily made a fire on a cliff nearby and were able to attract the attention of the whalers. Eyre and Wylie were received with great kindness and hospitality by Captain Rossiter, who commanded the French Whaler, the Mississippi.

In less than an hour, after watering the horses, they were on board the ship, surrounded by all the comforts of civilisation. It was such a change from the solitary loneliness and inconveniences of the desert that it seemed more like a dream. Comfortably bedded in a berth in the cabin, Eyre reflected on the goodness of God:

Sincerely grateful to the Almighty for having guided us through so many difficulties, and for the inexpressible relief afforded us when so much needed, but so little expected, I felt doubly thankful for the mercy we experienced, when, as I lay awake, I heard the wind roar, and the rain drive with unusual wildness, and reflected that by God's blessing, we were now in safety, and under shelter from the violence of the storm, and the inclemency of the wet season, which appeared to be settling in, but which, under the circumstances we were in but a few short hours ago, we should have been so little able to cope with, or to endure.[50]

Eyre and Wylie stayed with the captain on the Mississippi for two weeks. Wylie twice went out to try to shoot a kangaroo for the French whalers, but was unsuccessful. He had so much to eat he lacked the motivation to exert himself. On 14 June Eyre and Wylie landed their stores and packed ready for the remainder of the trip. The provisions consisted of:

Forty pounds of flour, six pounds of biscuit, twelve pounds of rice, twenty pounds of beef, twenty pounds of pork, twelve pounds of sugar, one pound of tea, a Dutch cheese, five pounds of salt butter, a little salt, two bottles of brandy, and two tin saucepans for cooking; besides some tabacco and pipes for Wylie, who was a great smoker, and the canteens filled with treacle for him to eat with rice.[51]

Eyre arranged for payment at King George's Sound. In addition, Captain Rossiter insisted on outfitting both Eyre and Wylie, at no charge, with comfortable warm clothing, including whatever Eyre fancied from the Captain's private wardrobe. Rossiter also gave them six bottles of wine and a tin of sardines. Overwhelmed with gratitude for his generosity and kindness, and marvelling at God's provision, Eyre said "goodbye" to the whalers.

Moving on through heavy rains and cold weather, the party arrived at Albany, on King George's Sound, three weeks later. Eyre watched the touching and joyous reunion of Wylie with his relatives and friends, as displays of deep affection and embracing were expressed by both sides.[52] Before his return to Adelaide, Eyre arranged for John Hutt, the Governor of Western Australia, to take care of Wylie, whom he believed was deserving of special honour. The Governor agreed and Wylie became a local hero.[53] For this incredible journey, Eyre was awarded the founder's gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society in 1847. The Society also published three of his papers.[54]

On his return to Adelaide, Eyre was received at a special public dinner given in his honour by Governor George Grey, himself a former explorer. The dinner was chaired by the famous explorer, Captain Charles Sturt, and attended by Mr E. Stephens and other notables. The Governor, in his speech, pointed out to the company the significance of Eyre's great achievement:

Mr Eyre has connected Captain Sturt's discoveries with the western coast of the continent; and it is rather singular, gentlemen, that the latter who commenced by himself between the eastern and western coasts of Australia, should be chairman tonight of the meeting to welcome one who has completed the geographical chain.[55]

Grey also commented on Mr Eyre's "dauntless courage" in the face of "difficulty after difficulty ... and danger was as it were his bedfellow". In addition to Eyre's qualities as an explorer, the Governor commended him for "his excellent private character and modest demeanour" and for "the fidelity and ability with which he described the country he has examined".[56]

In his response, Eyre concluded by saying that:

Man may indeed propose, but that it is God above who can dispose.... It has pleased His Almighty Wisdom to bar our progress into the interior; but I still feel that I have much reason to be most sincerely grateful to that merciful and protecting Providence which has guided me through so many difficulties and guarded me through so many dangers.[57]

Eyre had arrived back in Adelaide penniless and with no prospect of employment, so he was happy to accept a position as protector of the Aborigines on the Murray, with his headquarters at Moorundie. He had always been distinguished by his love for the Aborigines and for his success in his dealings with them.[58] From the time of Eyre's arrival in 1841 until he left, there was no case of serious injury or aggression of the natives towards the Europeans. This was a complete reversal of the previous situation. In 1844 Eyre took "temporary leave" to visit England, taking with him two Aboriginal boys to be educated in England at his own expense, but he never returned.[59] While in England, Eyre met a young lady who later became his wife, through what appeared to be a trivial circumstance. He later wrote:

Such are the mysteries and inscrutable ways of Providence and so impossible is it for man's private comprehension to estimate the result even of his own simplest actions, still less to judge of the more general ordinations of Divine wisdom. In my progress through life I have frequently found trivial circumstances conducive to important events, and influential occurrences take place when least expected; an experience no doubt shared in by others, but which I think ought to teach us to distrust ourselves and our own judgement and to place full reliance in the wisdom and goodness of God, who can, and in his own good time often does, make plain and clear what once seemed dark, inexplicable or unimportant.[60]

Eyre recognised the sovereignty of God operating in the lives of individuals and nations. So did Sturt, Leichhardt and Grey.

Sir George Grey's career as an explorer was brief, but deserves mention because he opened up the west coast from Perth to Shark Bay. The purpose of his explorations was to find out if there was a great river on the western coast. With support from the Royal Geographical Society, Grey landed at Hanover Bay, with the intention of proceeding south down to the Swan River settlement. On the way he would of necessity cross many rivers. In January 1838, the party moved slowly inland because of rainy weather. Grey was seriously wounded in an attack by Aborigines, and had to return to Hanover Bay and Mauritius to recover. Later, he made a second attempt from Shark Bay, using whaleboats in an attempt to land. Owing to gales, they lost their stores and then their boats, and were forced to march 300 miles to Perth under terrible conditions. Grey wrote in his journal:

I feel assured that but for the support I derived from prayer and frequent perusal and meditation of the Scriptures, I should never have been able to have borne myself in such a manner as to have maintained discipline and confidence among the rest of the party: nor in all my sufferings did I ever lose the consolation derived from a firm reliance upon the goodness of Providence. It is only those who go forth into perils and dangers, amidst which human foresight and strength can but little avail, and who find themselves, day after day, protected by an unseen influence, and ever and again snatched from the very jaws of destruction, by a power not of this world, who can at all estimate the knowledge of one's own weakness and littleness, and the firm reliance and trust upon the goodness of the Creator which the human breast is capable of feeling.[61]

Grey was a devout Anglican and helped to develop the New Zealand Church Constitution.[62] He was the first explorer to publish drawings and descriptions of Aboriginal art. He is best known for his distinguished public service career, first as Governor of South Australia, and later as Governor of the Cape Colony, and Governor and Premier of New Zealand.

Charles Sturt opened up south-eastern Australia, and John Edward Eyre completed the path to the west coast, with Grey charting part of the western coastline. On the other hand, Fredrich Wilhelm Ludwig Leichhardt explored the country to the north of New South Wales. Like his two predecessors, he was a man of simple Christian faith, and openly acknowledged Jesus Christ as his personal Saviour.

Probably the most extraordinary and eccentric of all the Australian explorers, Ludwig Leichhardt was born on 23 October 1813 at Trabatsch in Prussia. He was the son of Christian Hieronymus Matthias Leichhardt, farmer and inspector of peat-cutters, and Charlotte Sphie, nee Strahlow. He was educated at the universities of Berlin and Gottingen. At Gottingen he met Englishman John Nicholson, who was studying medicine. As a result of their friendship, Leichhardt became interested in natural sciences, which he studied for their own sake without following a degree program. Although he never received a university degree, Leichhardt was later addressed as "doctor" because people recognised he was a man of learning.

In 1837 Leichhardt visited England, where he stayed with John's brother, William Nicholson. For the next three years Leichhardt and William travelled and studied together in Europe. When Leichhardt was called up for military service, he decided instead to emigrate to Australia. He had been fascinated by the reports of the extraordinary plants and animals found there, so he saw it as an opportunity to further his study in the natural sciences. William paid Leichhardt's passage and gave him 200 pounds. On arriving in Sydney he stayed for a while with William's youngest brother, Mark. Leichhardt was unable to find employment, but found another benefactor in Robert Lynd, whom he described as "a substitute for William, sent by Providence".[63]

In 1842, a wealthy squatter, Walker Scott, invited Leichhardt to spend some time in Newcastle on the Hunter. As an "explorer of nature", wherever Leichhardt went he studied the plants, the geological objects and animals, and made excursions in all directions. To Leichhardt it was serious business--a divine call. In a letter to his sister, he wrote:

If nature stirs you to such pleasure, just think how she must stir me, in my chosen task of penetrating her secrets and discovering the laws that govern the everlasting might and splendour of her workings! Would it not be sin in me to give you any other answer but that of our Redeemer to his anxious Mother when she found him in the temple? 'Wist ye not that I must be about my Father's business?'[64]

Leichhardt bought himself a horse and rode up the Hunter River Valley, and began to gain some bush and farming experience. Scott offered him a job managing a vineyard for one hundred pounds a year with a cottage, but Leichhardt decided against settling down before seeing all parts of the colony. In 1843-44 Leichhardt made overland journeys alone between Newcastle and Moreton Bay (Brisbane), a distance of 600 miles.

In May 1844 he returned to Sydney to organise his plant and rock collection and to work on his notes. He made plans to accompany an overland expedition, headed by Surveyor-General Sir Thomas Mitchell, from Sydney to Port Essington in Arnhem Land, a distance of 3000 miles. When Governor Gipps would not approve of the plans for such an expensive expedition without the consent of the Colonial Office, Leichhardt decided to organise his own expedition. It seemed a foolhardy plan that a young short-sighted German, with a poor sense of direction and unable to use a gun, should dare to lead an expedition of such magnitude. He had little bush experience. However, foolish as it seemed, Leichhardt possessed resolution and faith in himself and God. He was able to attract private support and volunteers. It was a strange crew, "buoyant with hope", that set out from Jimbour station, north-west of Brisbane on 1 October 1844.

The party consisted of ten men, of whom seven completed the journey. They had with them 17 horses, 16 bullocks, 1200 pounds of flour, 200 pounds of sugar and 80 pounds of tea. Hampered by poor leadership and lack of experience, they had difficulties from the beginning. When Leichhardt led them in a dash through the scrub in an attempt to find a river flowing westwards, they lost 15 pounds of flour, 143 pounds of sugar, and other valuable provisions. (They scraped up the flour with gum leaves and made a delicious stew of flour mixed with leaves and dirt!) Other troubles followed, but the party pressed on and discovered and named many important rivers, ranges and extensive pastoral country. They followed the Burdekin River, Lind River and Mitchell River, and had almost reached the western coast of Cape York Peninsula when some Aborigines attacked them. Naturalist John Gilbert was killed and two other members of the party were wounded. From then on Leichhardt followed the coast closely, skirting the southern banks of the Gulf of Carpentaria to the Roper River, his last important discovery. Crossing Arnhem Land, the party wearily headed for Port Essington. In the last stages of their journey the men were only concerned with survival. They arrived at their destination after a journey of 14 months and 17 days from Jimbour. They returned by sea to Sydney, where they were acclaimed as men "back from the grave", and overnight they became national heroes.

Leichhardt's expedition proved to be very important because of the vast amount of country he opened up in the north. He made two other journeys in an attempt to cross the northern part of the continent and to travel down the west coast to Perth. The second expedition left the Darling Downs in December 1846, but after eight months they accomplished nothing. They had to return because of bad weather, illness and quarrelling. Leichhardt was not a man to give up easily, however, so he organised a third expedition, which left from Roma in April 1848. Leichhardt's last letter was dated 4 April 1848. He was headed north or north-west, but he and his party were never heard of again. Search after search failed to reveal a trace of the seven missing men, 50 bullocks, 20 mules and seven horses.

Leichhardt's great contribution to the history of Australian exploration is unquestioned. His first journey was useful in the discovery of "excellent country available ..E. for pastoral purposes". He is known as the most important of the scientific explorers. The Royal Geographical Society awarded him its Patron's medal in recognition of "the increased knowledge of the great continent of Australia", gained by his Moreton Bay-Port Essington journey. The King of Prussia recognised this achievement by pardoning him for failing to report for compulsory military service. Leichhardt left records of his observations in Australia from 1842 to 1848 in manuscript diaries, letters, notebooks, sketchbooks, maps, and in his published works.[65] His lively but detailed letters included many valuable scientific observations (especially pertaining to biology, geology and geography).[66] Leichhardt's journal is a detailed description of his first overland expedition.[67] The documents he left can be examined.

An assessment of Leichhardt's character is more difficult; it remains as ambiguous as his fate. However, the reader can know something about his faith. Raised in a Lutheran home, he was known to be a man of simple Christian faith and moral character. He remembered with affection the church of his childhood, but hated religious controversy. He found "sufficient" the statement of faith: "I believe in Jesus Christ our Saviour".[68] In a letter dated 6 September 1842 he confided to his mother:

I feel as innocent as I was when you last took me in your arms. And I have you to thank for it. [Why? Because] when I think of the source of my moral principles what comes to mind is the room with the tiny little window in our old house, where you taught us to say our prayers morning and evening, and made us aware of our Father which art in Heaven.[69]

Leichhardt often thought of his mother's parting words: "My son, the Lord will not abandon you", as he trudged on with renewed courage to the next campsite. At night, as the horses were unharnessed, hobbled, washed down, and sent out to feed, the fire was lit and the billy was boiling, Leichhardt would stretch out his weary body on the hard ground and look up at the cloudless sky as the stars came out. Before he dozed off to sleep, he would offer a prayer of thankfulness to God for His goodness. Many such prayers went up from that unknown northern coast under the Southern Cross.[70]

The last words of Leichhardt, in a letter dated 3 April 1848, from McPherson's station on the Cogoon, are a reaffirmation of his faith:

Seeing how much I have been favoured in my present progress, I am full of hopes that our Almighty Protector will allow me to bring my darling scheme to a successful termination.[71]

If it would seem that the Almighty Protector failed Leichhardt that time, the reader is reminded of other men of faith, like Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, who "died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth"(Heb. 11:13).

Since the discovery of Gilbert's journal in the 1930s, controversy has raged about Leichhardt's integrity, disposition and habits.[72] In spite of his failings as an administrator and leader of men, Leichhardt was a man of resolution, vision, courage and enterprise. Though a complex character, he was a man of practical Christian faith. Many more able men would have sat safely at home. He deserves to be commended for what he did. He dared and died in action, as did many who followed him.

Stuart's major contribution was his discovery of a practical route from the south to the north of the continent in 1861-62. Although Burke and Wills had been the first to do it, their route was not practicable except in a very wet season. Stuart was the first to discover an all season route, which was later used for the Overland Telegraph from Adelaide to Darwin. His extraordinary expedition was made with horses while Burke and Wills had used camels.[75] Stuart was a man of indomitable perseverance and courage. Though his sufferings were sometimes almost intolerable, he would not give up. One of the party, William Patrick Auld, said: "I don't believe any other man could or would have travelled with the frightful agonies that Stuart suffered. He said to me, 'We must go on. If the party stop to nurse me, not one of you will ever reach the settled districts; there is not a day to spare. The waters are drying up.'" He was entirely devoted to his duty. Stuart himself had said: "I was determined to succeed or to die in the attempt". He suffered from scurvy and the intense heat. His eyes were so painful, that there were some days he could not see. He was near death several times, and he never fully recovered his health.

What kept him going? Stuart, like his predecessor, Charles Sturt, acknowledged his reliance on God, as excerpts from his journal show: "The sky is overcast and I trust that Providence will send us rain in the morning". Again: "About an hour before sundown, they arrived at the water, without any more losses, for which I sincerely thank God". Other excerpts from Stuart's journals also give an indication of the inner source of his strength. When the party reached the Indian Ocean, he wrote: "Thus have I, through the instrumentality of Divine Providence, been led to accomplish the great object of the expedition". Following the long return trip south to Adelaide, Stuart noted: "I sincerely thank the Almighty Disposer of Events that He, in His infinite goodness and mercy, gave me strength and courage ... and has kindly permitted me to live yet a little longer".[76] Stuart opened the way for others such as Peter Warburton to follow.

Peter Egerton Warburton was the son of a clergyman, and born in Cheshire, England. He served in the military in India until 1853, rising to the rank of major. He emigrated to Australia, where he became Commissioner of Police until 1867, when he became Colonel Commandant of the South Australian volunteer forces. His first venture in exploration was to map Lake Torrens, which had been such a puzzle to Eyre.

In 1872, Warburton planned an expedition from Adelaide to Perth, via Alice Springs (1610 kilometres north of Adelaide over known territory). The party consisted of Warburton, his son Richard, two white men, an Aboriginal lad, Charley, two Afghan camel drivers, and seventeen camels. After leaving Alice Springs, Warburton had planned to take a south-westerly route, but he was forced to travel north-west because of a water shortage due to the drought. The men went through incredible hardships. The heat was so intense that they could only travel at night, while sleep was almost impossible because of thousands of tormenting ants. Warburton had food supplies for six months, but it took them ten months to reach the Oakover River in north-western Australia. They were able to save their lives by getting in touch with some settlers.[77]

A reading of Warburton's Journal across the Western Interior of Australia reveals that the expedition revolved around a search for water and food. Journal entries give detailed accounts of their diet. Warburton apologised for his obsession with food, but added that if a person is starving, that is all he can think about! It was an incredible journey, and Warburton was quick to recognise the hand of God in preserving their lives. Throughout his journal, there are many phrases acknowledging their dependence on Him as their source of supply: "We can only hope to prolong our lives, as God may enable us, on sun-dried camel flesh ... and should it please God to give us more water".[78] Warburton was a man of faith. "We are in the hands of God, and there is always hope while there is life. I am thankful to say I have neither fear nor fretfulness. I am not afraid of evil tidings....God grant us strength to get through!"[79]

Warburton described one instance in which Divine supervision was clearly apparent. Warburton had been reduced to a skeleton by thirst, famine and fatigue. He was so emancipated and weak that he could barely get up and stagger a few steps. Charley had been sent to find water; Warburton was worried about him because he had not returned at sunset, when they were ready to leave. To delay meant death to them because they did not have enough water to carry them through the night. On the other hand, to leave the camp without Charley would be inhuman as he would die. Warburton did not know what to do. It was six to one, so they waited until the moon was well up, and left at 9.00 p.m. The men had gone about eight miles, when they heard a "cooee", and to their great delight, Charley ran up, panting. He had tracked down a party of friendly natives and had gone to get their water, and run all twenty miles back, though he was already exhausted from travelling all night before.

Warburton noted: "It may, I think, be admitted that the hand of Providence was distinctly visible in this instance". He had decided to wait until 9.00 p.m., hoping that Charley would be back by then. If they had left ten minutes earlier or ten minutes later, they would have missed Charley because the route taken by Charley was at right angles to that taken by Warburton and the men. The odds of them stumbling across each other in the dark were "infinitesimally small". If Charley had missed them, there was little doubt in Warburton's mind that he and probably other members of the expedition would have died from thirst.

Providence mercifully directed it otherwise, and our departure was so timed that, after travelling from two to two hours and a half, when all hope of the recovery of the wanderer was almost abandoned, I was gladdened by the 'cooee' of the brave lad, whose keen ears had caught the sound of the bells attached to the camels' necks. To the energy and courage of this untutored native may, under the guidance of the Almighty, be attributed the salvation of the party. It was no accident that he encountered the friendly well....I was so utterly exhausted when we camped at 3.00 a.m., it was evident I never could have gone on after that night without more food and water. I would therefore thankfully acknowledge the goodness and mercy of God in saving my life by guiding us to a place where we got both.[80]

Under such terrible desert conditions, Warburton and his party were daily dependent on God. Five days later, when they were again at their last drop of water and Warburton choked on the smallest piece of dried camel meat, he noted: "Unless it please God to save us, we cannot live more than twenty-four hours.... God have mercy upon us, and by the time death reaches us we shall not regret exchanging our present misery for that state in which the weary are at rest".[81]

God provided--sometimes a waterhole, a native well, a hidden spring. Their staple diet, having exhausted the supplies they had brought with them, was dried camel meat. Concerning the death of a camel, Warburton commented: "I hope the fact of the camel's head not having been turned towards Mecca, or its throat cut by a 'True Believer', may not prejudice the camel-men against the use of what we send".[82] Nothing was wasted. When they killed a camel, they ate the heart and liver for supper and boiled kidneys and tongue for breakfast! They made a soup, which was a favourite of Charley's, from the head, tail, liver, heart and kidneys. Camel's foot was a delicacy. As they travelled, the men were always on the lookout for some variation in their diet--a fish, a cockatoo, a little bird, small native fruit, or bullrush roots roasted in ashes or boiled. It was difficult to find a snake, a kite or a crow. There were a few wallabies in the spinifex (a coarse spiny grass), but they were not able to catch them.

On 17th (month?), they found two large seashells, and an old iron tomahawk, and part of a tyre from a dray--a hopeful sign of approaching civilisation. Three weeks later, they reached the Oakover River. The men were so weak from scurvy and diarrhoea they were unable to walk. They had just eaten their last camel, and though there was plenty of fish and wildlife, they were unable to get it. "We have fish close to us, but though we deprive ourselves of the entrails of a bird as bait, they will not take it. We eat everything clean through, from head to tail".[83]Warburton complained because they could not catch the fish, find opossums or snakes, and the birds would not sit down beside them! They were hoping the late rain would bring up some thistles or pigweed to eat. Warburton had sent Lewis and one Afghan on the only two camels that would travel, to look for the station of Messrs Harper and Co., 274 kilometres down the river, to get supplies. They had no assurance that it was not abandoned, nor of how long it would be before they would return. Warburton noted: "Our lives have been preserved through many and great dangers, so my trust is in God's mercy towards us; it never fails, though it does not take always the course we look for".[84] A few hours after making the above entry, Lewis returned with ample supplies for all their needs, and six horses to carry them down. For his labours, Warburton was awarded the Royal Geographical Society 's medal, and received a grant of money from the South Australian Government.

Another man who helped open up Western Australia was Sir John Forrest, first Baron of Bunbury, surveyor, explorer and politician. He was born to Scottish immigrants at Bunbury, Western Australia. Forrest and his eight brothers worked on their father's farm. John was educated in Perth and became a surveyor for the Western Australian Government.

In 1869, to confirm reports that the lost Leichhardt of twenty years before had reached Western Australia where he had been murdered by Aborigines, John Forrest set out from Perth to investigate. The expedition reached the 123rd meridian of east longitude, but found no trace of Leichhardt.

In 1870 Forrest made a second expedition from Perth to Adelaide, following the same coastal route around the Great Australian Bight as John Eyre had thirty years earlier. It was the first west-to-east crossing by land and resulted in the construction of a telegraph line along the coast, putting Perth in telegraphic contact with London.

However, John Forrest is more famous for his 1874 expedition which made him the first explorer to cross Western Australia from west to east, taking an interior route across the central desert. He left Geraldton with six men and twenty horses, moving strategically from waterhole to waterhole. Occasionally they found a spring, which was "quite a diamond in the desert". The weather was intensely hot, and as they had only three riding horses (the others were used to carry supplies), three of the men had to walk. As horses must have water every twelve hours, much valuable time and energy was used looking for water, which often entailed weary deviations from the main route and many disappointments. (Warburton, who had attempted to cross the desert from the east, had used camels that can go for twelve days without a drink.) In face of the many hardships, Forrest "endured as seeing Him who is invisible". Evidence of his Christian faith and character is shown in his journals.

[19 April 1874] The 19th was a Sunday, and according to practice, we rested every Sunday throughout the journey. I read Divine Service, and, except [for] making the daily observations, only work absolutely necessary was done. Whenever possible, we rested on Sunday, taking, if we could, a pigeon, a parrot, or such other game as might come in our way as special fare. Sunday's dinner was an institution for which, even in those inhospitable wilds, we had a great respect.[85]

Forrest's instructions had been to find suitable pasture lands for grazing, but he did not find much besides spinifex and more spinifex and little water. The party had several narrow escapes from death by thirst and hostile Aborigines. Forrest noted:

[?17 September] It is in circumstances such as I am at present placed that we are sure to implore help and assistance from the hand of the Creator; but when we have received all we desire, how often we forget to give Him praise![86]

Five months and 2700 miles after leaving Champion Bay, Forrest arrived at Peake Hill on the north-south overland telegraph line between Adelaide and Port Darwin. Loud cheers went up from the little party when they sighted their goal. Forrest commented:

[27 September] I felt rejoiced and relieved from anxiety; and on reflecting on the long line of travel we had performed through an unknown country, almost a wilderness, felt very thankful to that good Providence that had guarded and guided us so safely through it.[87]